On Exhibit

Our national museum strengthens the understanding of who we were in the past, are in the present and will be in the future, reinforcing traditional foundations while providing paths for personal, communal and cultural expression.

Recipient of the Museum Institutional Excellence Award by the Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums

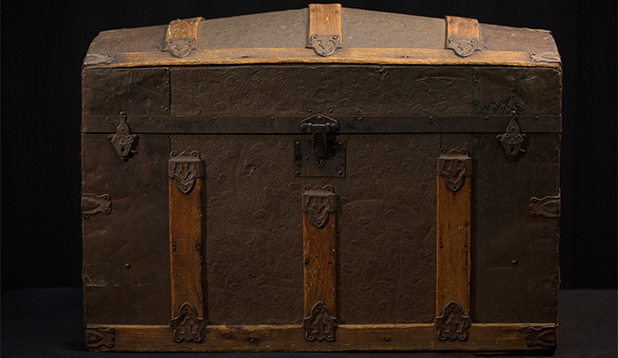

bmodéwzewen (footlocker) ca. 1895 Courtesy: Cultural Heritage Center

Bmodéwzewen (footlocker)

Displayed in the Cultural Heritage Center’s Indian Territory: A Place to Call Our Own gallery is the personal bmodéwzewen (footlocker) of David P. Johnson, when he attended Carlisle Indian Industrial School [Pennsylvania] from 1895-1899. The camel back trunk is made of wood, metal and leather. Embossed on the latch is the patent date, July 9, 1872. Stenciled on the side of the footlocker is, Indian School: Carlisle, PA.

Symbolizing the hardships our young people endured, viewing the footlocker evokes mixed emotions and memories for many. To serve as a historical testament of strength to the community, Richard V. Johnson, son of David P., donated his father’s footlocker to the CHC in 2007.

bgemagen (war club) by Bud Onzahwah ca. 1980’s Courtesy: Cultural Heritage Center

Bgemagen (war club)

Within the CHC’s permanent collection is a contemporary artifact modeled after an ancient style of Potawatomi war club, known as a bgemagen, created by tribal member Bud Onzahwah. Crafted from wood, stone and leather, its historically ergonomic design eased storage, travel and use during battle.

Warfare comprises a large part of Potawatomi history, especially after colonialism, as communities aggressively protected their way of life and remained spiritually in balance. However, battles were not commonly fought during the winter months. Warriors had to maintain the wellbeing of their families and communities by securing ample resources to survive the winter. The winter season was also a time when life slowed and began its cycle of rejuvenation. Once the world reawakened and temperature rose, disputes could resume.

Pre-dating the use of firearms and used continually after their introduction, Potawatomi used and refined a battle tactic commonly known as volley fire to maximize enemy casualties. Implementing the tactic, Potawatomi wédaséjek [warriors] would ambush their enemies, firing a simultaneous shower of either arrows or rounds into the center of the unsuspecting formation. Once initial surprise and disorder was achieved, wédaséjek would charge the enemy, engaging in hand-to-hand combat using their war clubs.

![Gété Neshnabek Zhechgéwen [bbon] gallery 2017 courtesy: Cultural Heritage Center](https://www.potawatomiheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/On-Exhibit-Agmek-snowshoes-scaled.jpg)

Gété Neshnabek Zhechgéwen [bbon] gallery 2017 courtesy: Cultural Heritage Center

Agmek (snowshoes)

Displayed in the Cultural Heritage Center’s Gété Neshnabek Zhechgéwen (Lifeways) gallery are some of the oldest known survival tools in North America, agmek or snowshoes. The design and use of snowshoes have evolved throughout the Northern Hemisphere for more than 6,000 years. On Turtle Island, four main styles are recognized: Algonquin or Huron, Bear Paw, Alaskan and Beaver Tail or Nishnabé. Additionally, a greater number of more specialized and hybridized versions are crafted by communities to serve uniquely specific purposes. Each style is relative to the terrain and environment that respective communities navigated in the past and present, such as flat prairies, rolling hills or mountainous ranges.

The CHC’s agmek were crafted of black ash by lifeways specialist, Jim Miller, in consultation with Pokégenek Bodéwadmik artisan and knowledge keeper, Frank Barker. They were specifically commissioned for exhibit in the Gété Neshnabek Zhechgéwen gallery, illustrating the ingenious and innovative ways our ancestors traversed the world around them.