Galleries

Explore the rich history and vibrant culture of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation through our museum galleries – preserving stories of resilience and tradition.

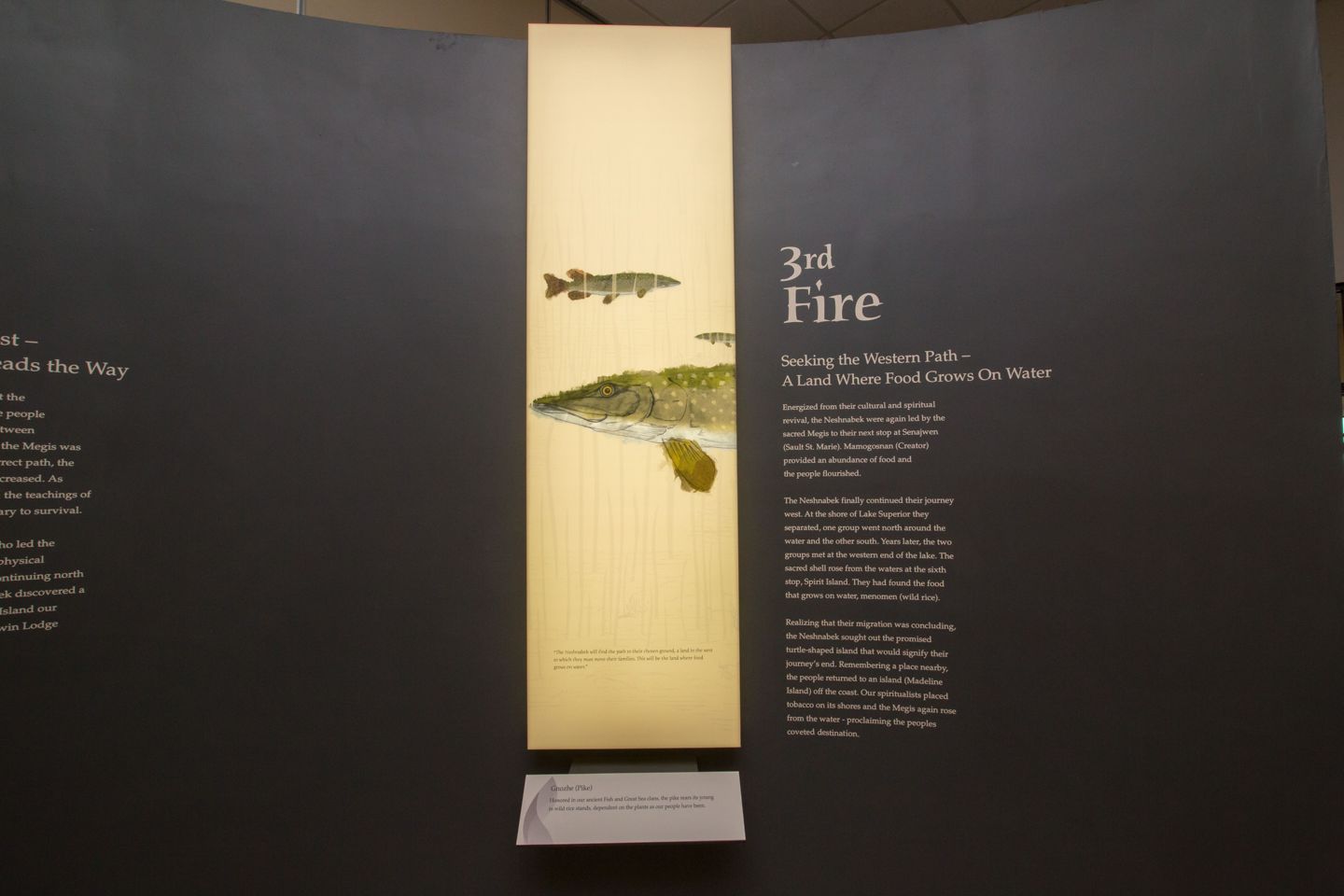

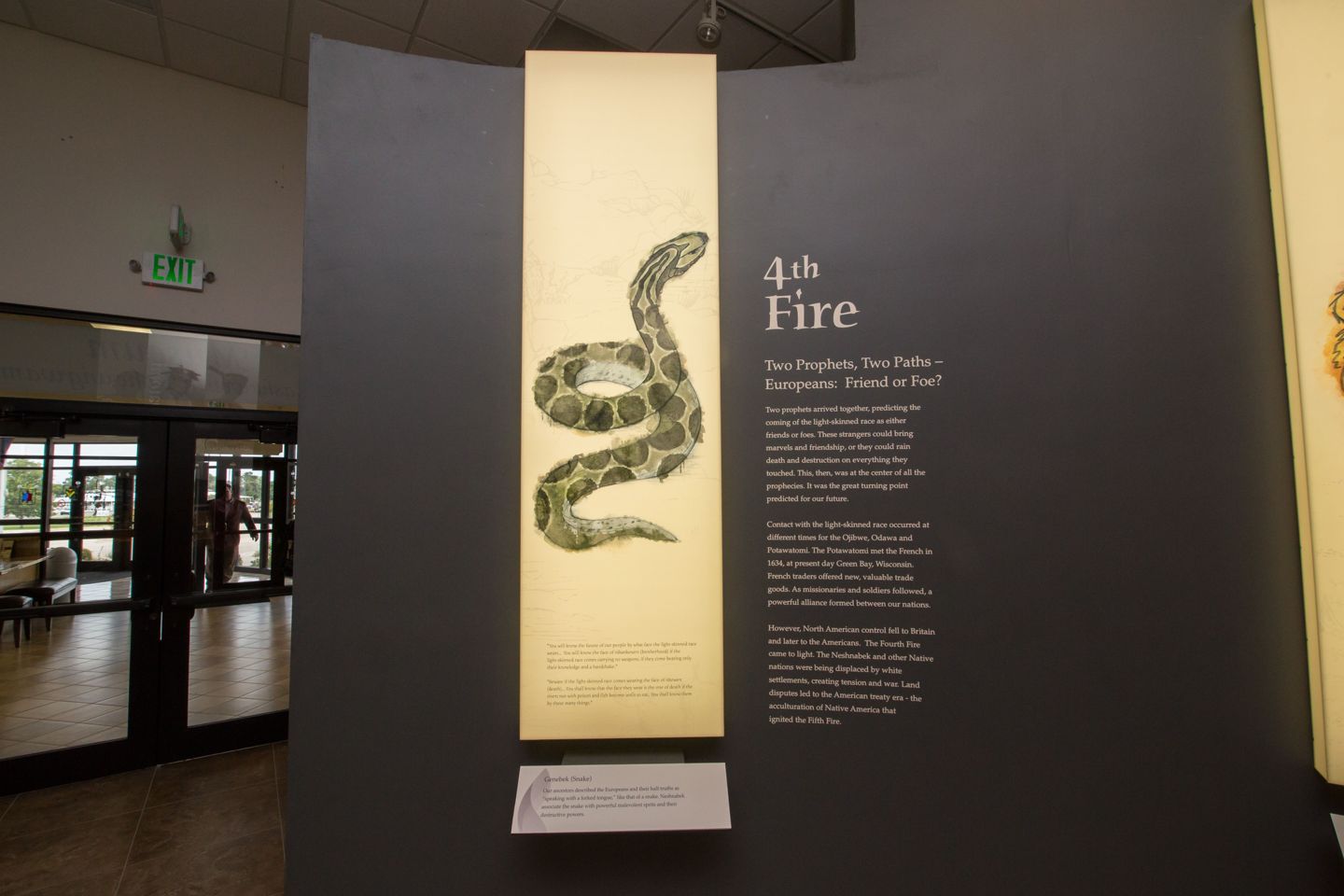

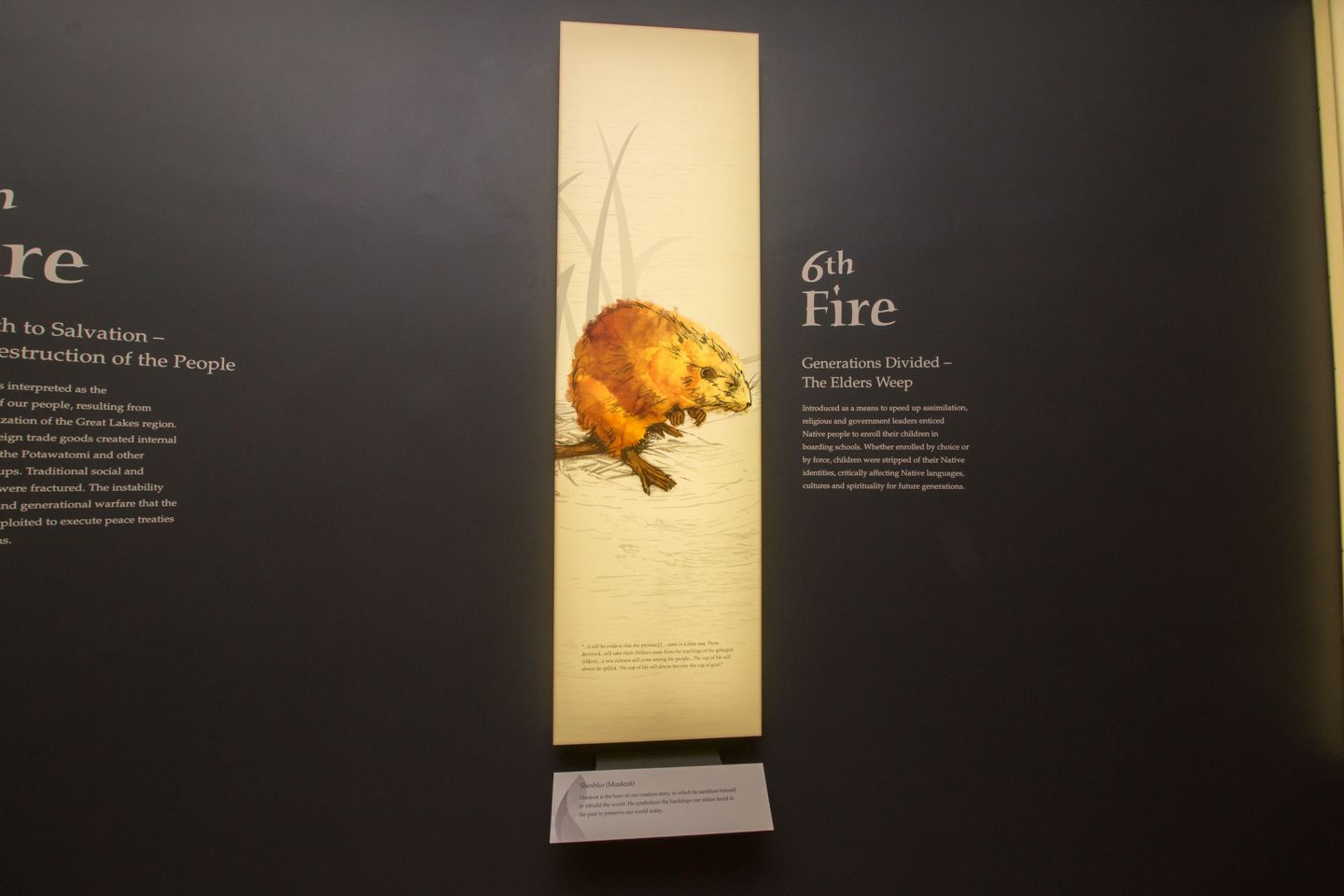

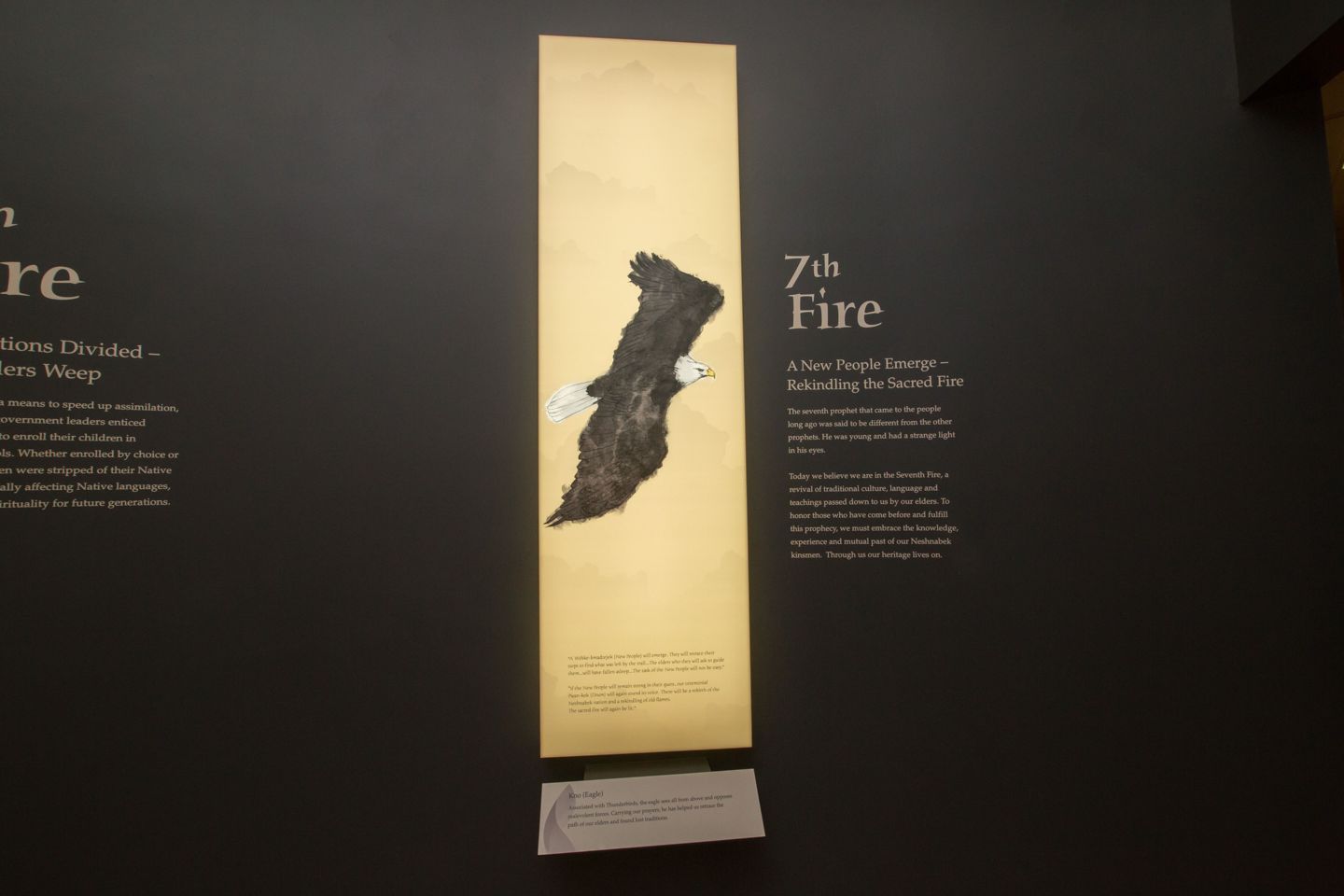

Seven Fires

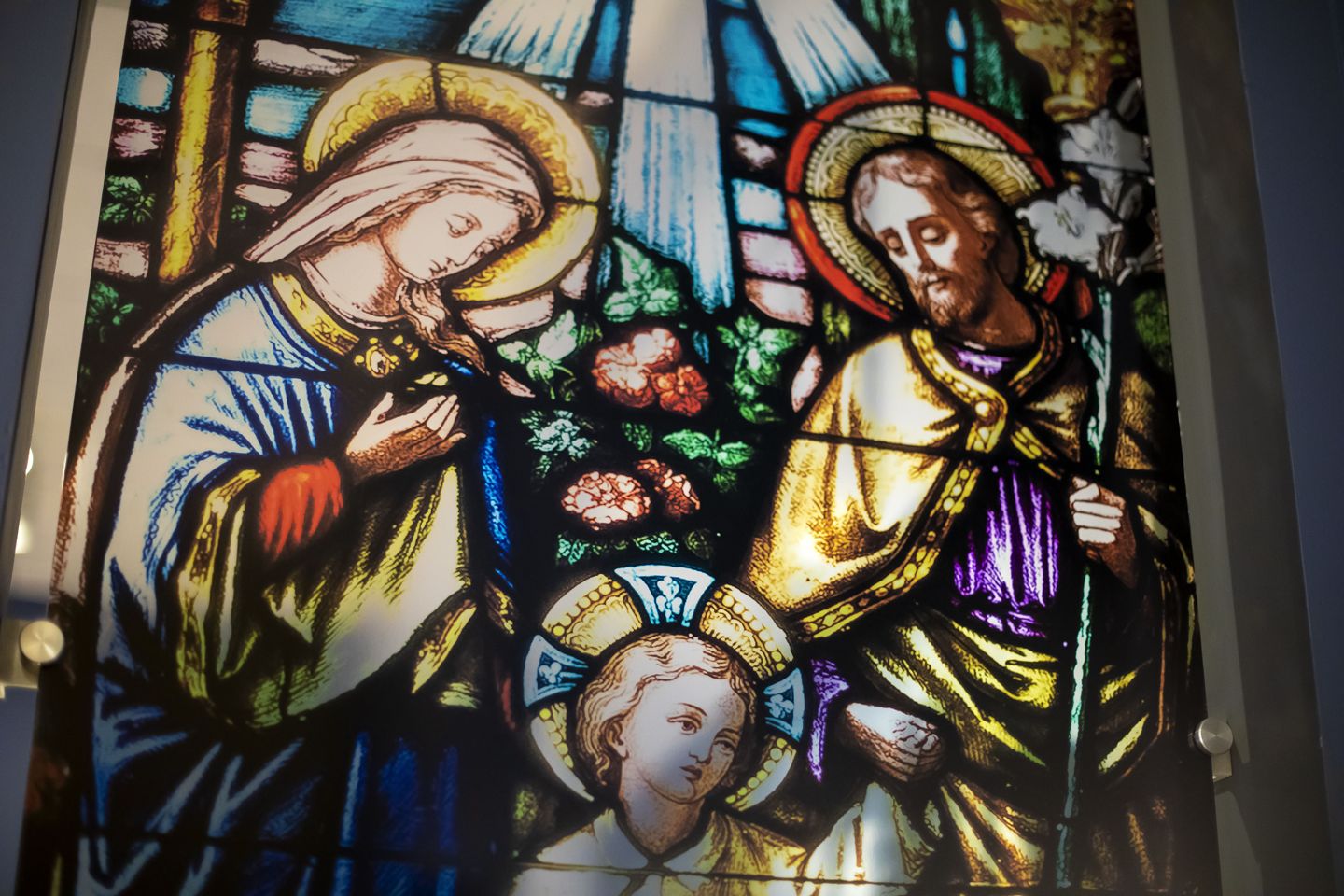

The story of Potawatomi and other Nishnabe peoples stretches back centuries. The Potawatomi, along with the Odawa and Ojibwe, were once living in the northeastern corner of the United States as one people known collectively as Nishnabe. Seven prophets came to the Nishnabe. Each spoke of key eras that the Potawatomi have endured including the Nishnabe migration to the Great Lakes Region, European arrival, loss of culture and eventual rekindling in the seventh and final fire.

Mamogosnan’s Gifts: Origins of the Potawatomi People

Generations of Potawatomi preserved history and culture through spoken language and the art of oral traditions. Stories and interactive videos highlight narratives that record Potawatomi beliefs, culture, history and early way of life. Each video is designed to allow visitors the opportunity to hear and interpret these early narratives for themselves — just like the Tribe’s oral traditions have existed since the dawn of time — and preserves important cultural teachings for generations to come.

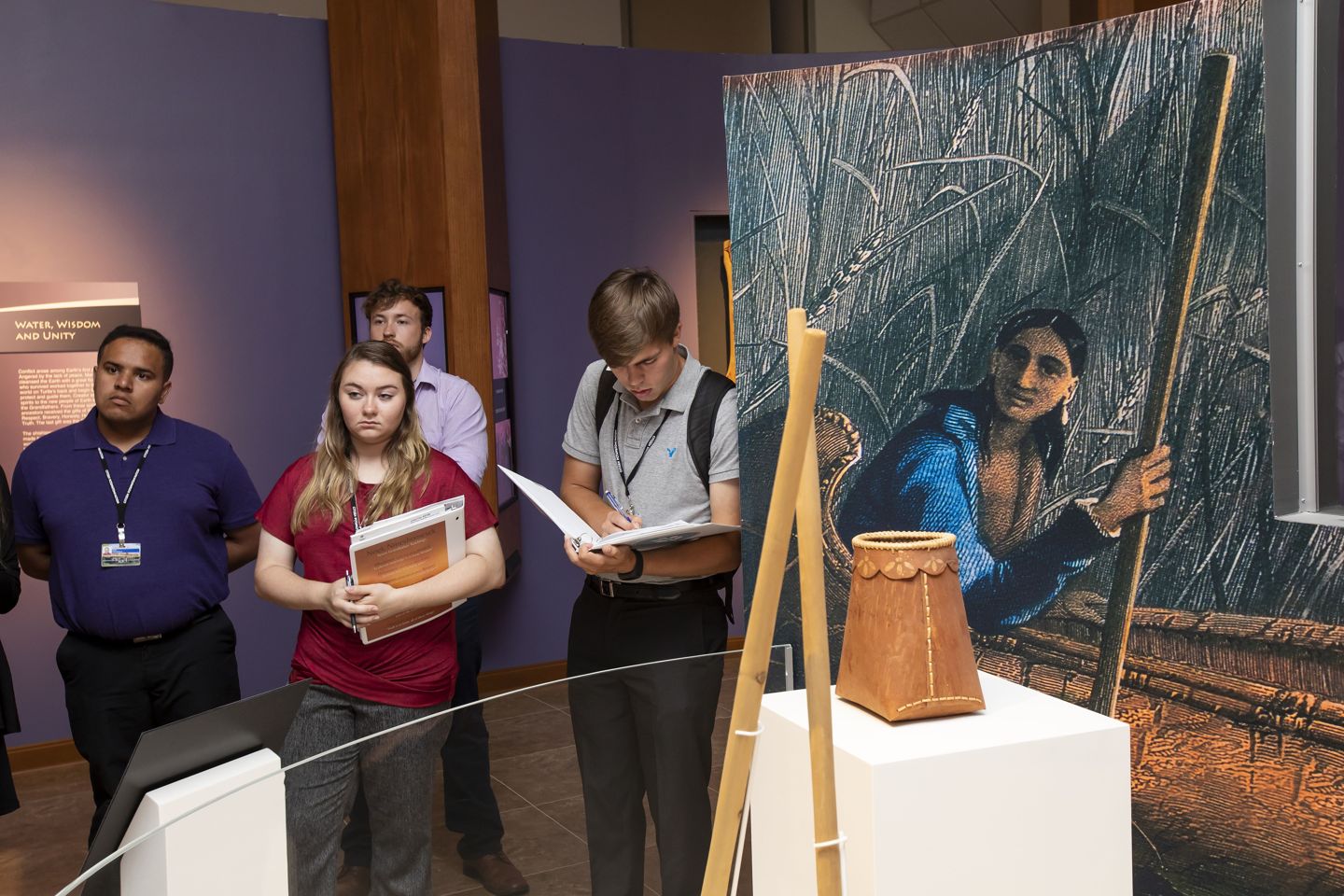

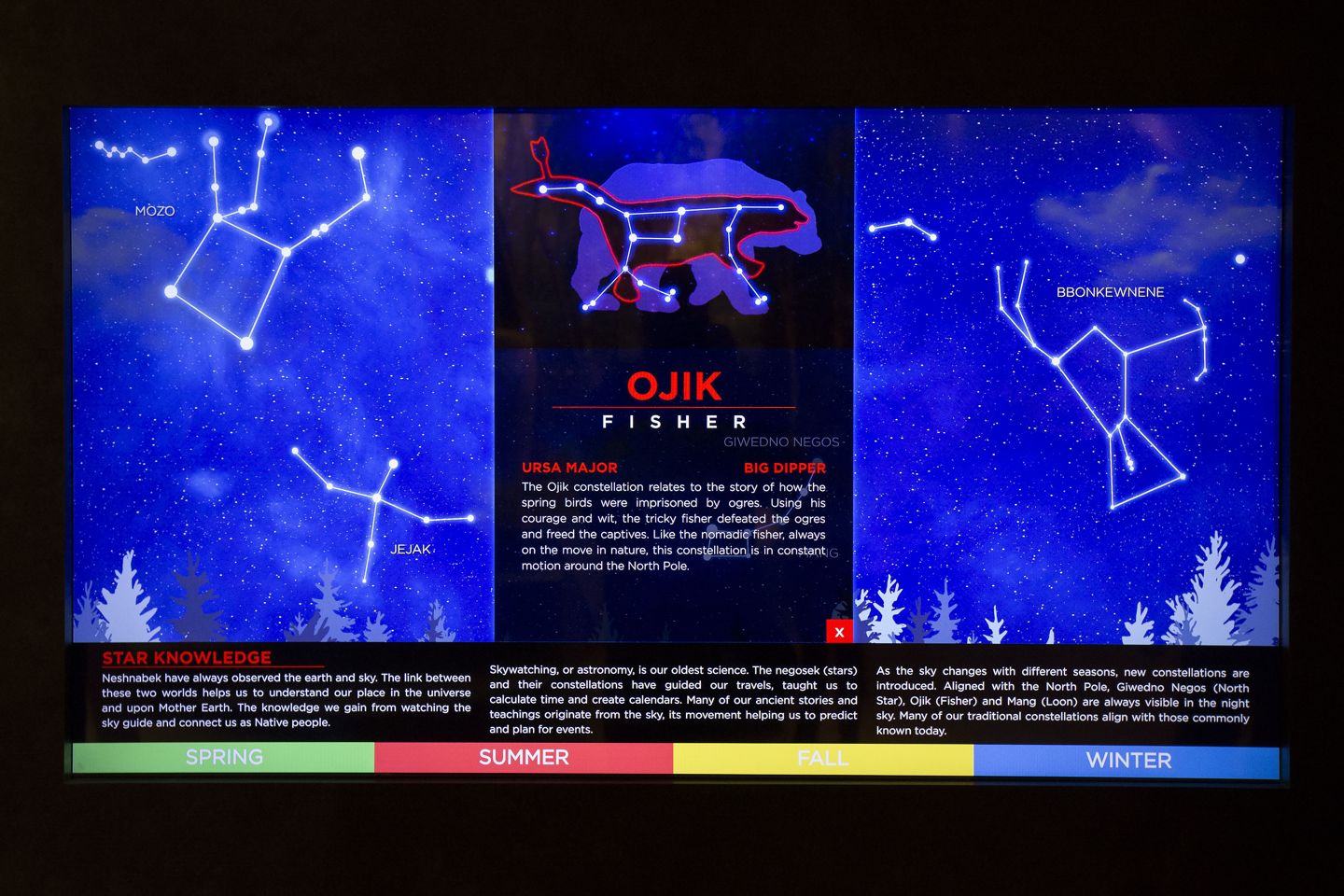

Gete Neshnabek Zhechgéwen

Gete Neshnabek Zhechgéwen evokes the senses and highlights the balance held between the Potawatomi, the earth, and pieces of culture kept alive despite centuries of unrest.

The Gete Neshnabek Zhechgéwen gallery features a wigwam as well as four interactive displays that help teach about Potawatomi medicine, the four directions, traditional hand games and star knowledge.

Strangers On Our Shores: Friend or Foe?

Early European contact ushered in an era of great change for the Potawatomi people. While European settlement allowed new alliances and lucrative avenues of trade to develop, it also caused new conflicts over territory and resources that resulted in an exodus by the Native population to avoid the political and social instability. European settlement significantly constrained Native mobility, causing fighting and destruction of old alliances, all of which greatly hindered the structure of tribal communities.

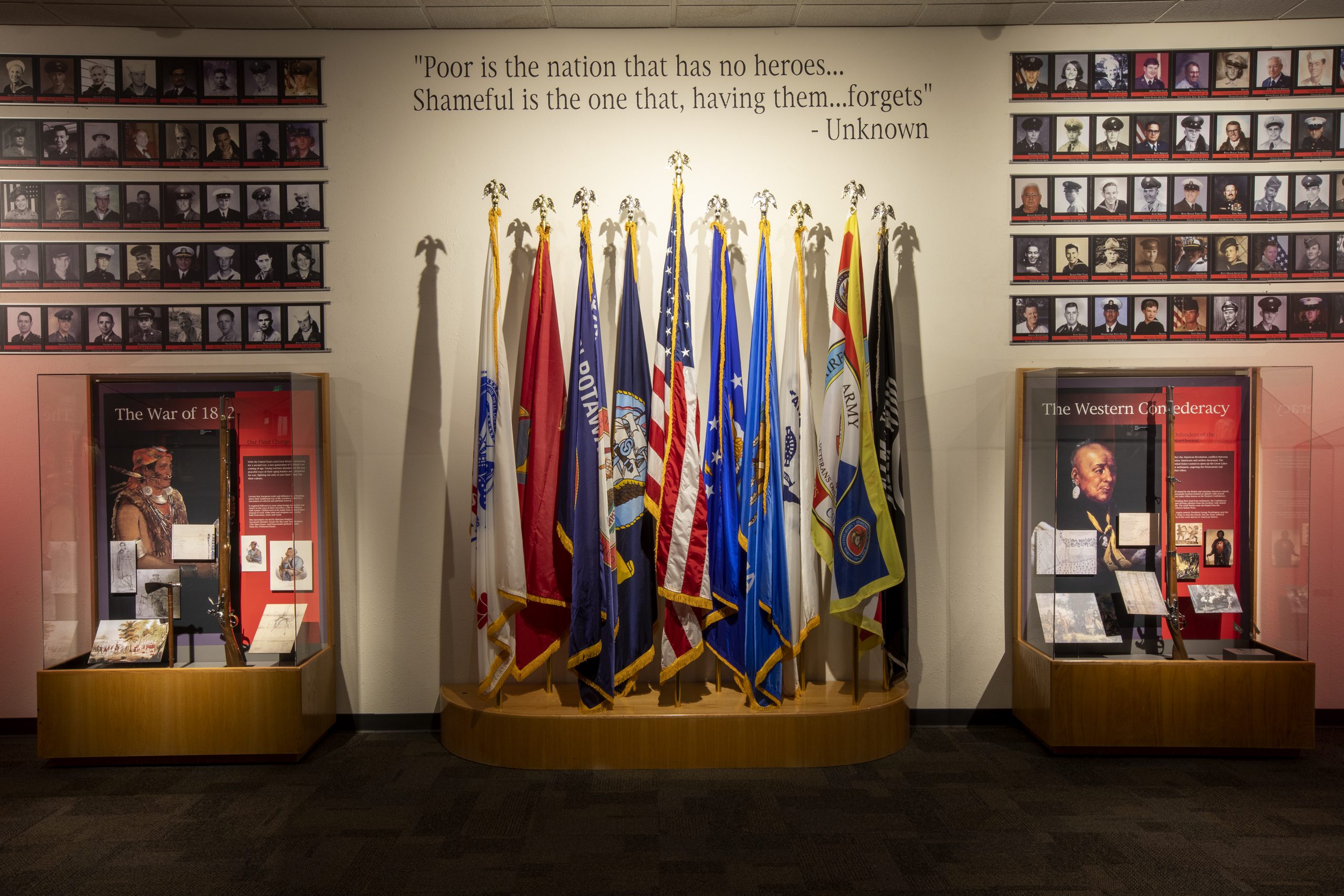

Defenders of the Northwest: Ndobani

Through the 18th to early 19th century, the fur trade’s decline and colonial competition increased discord among Native Americans and non-Natives. Each Native group had their own survival tactics. Some wanted to find the best European ally, while others tried to abandon colonialism entirely.

Native communities, including the Potawatomi, fought to preserve what they could to keep their culture, language and its people alive.

Treaties: Words & Leaders That Shaped Our Nation

Following the War of 1812, the post-war terms of the relationships between tribes and the United States were determined. The Constitution dictated that the federal government, not those of states or municipalities, had the authority to negotiate treaties with tribal governments. Violence and hunger for tribal land resulted in more than 200 peace and land cession treaties in the first few decades of the new nation’s independence. The Potawatomi were signatories to over 40 treaties, more than any other tribe.

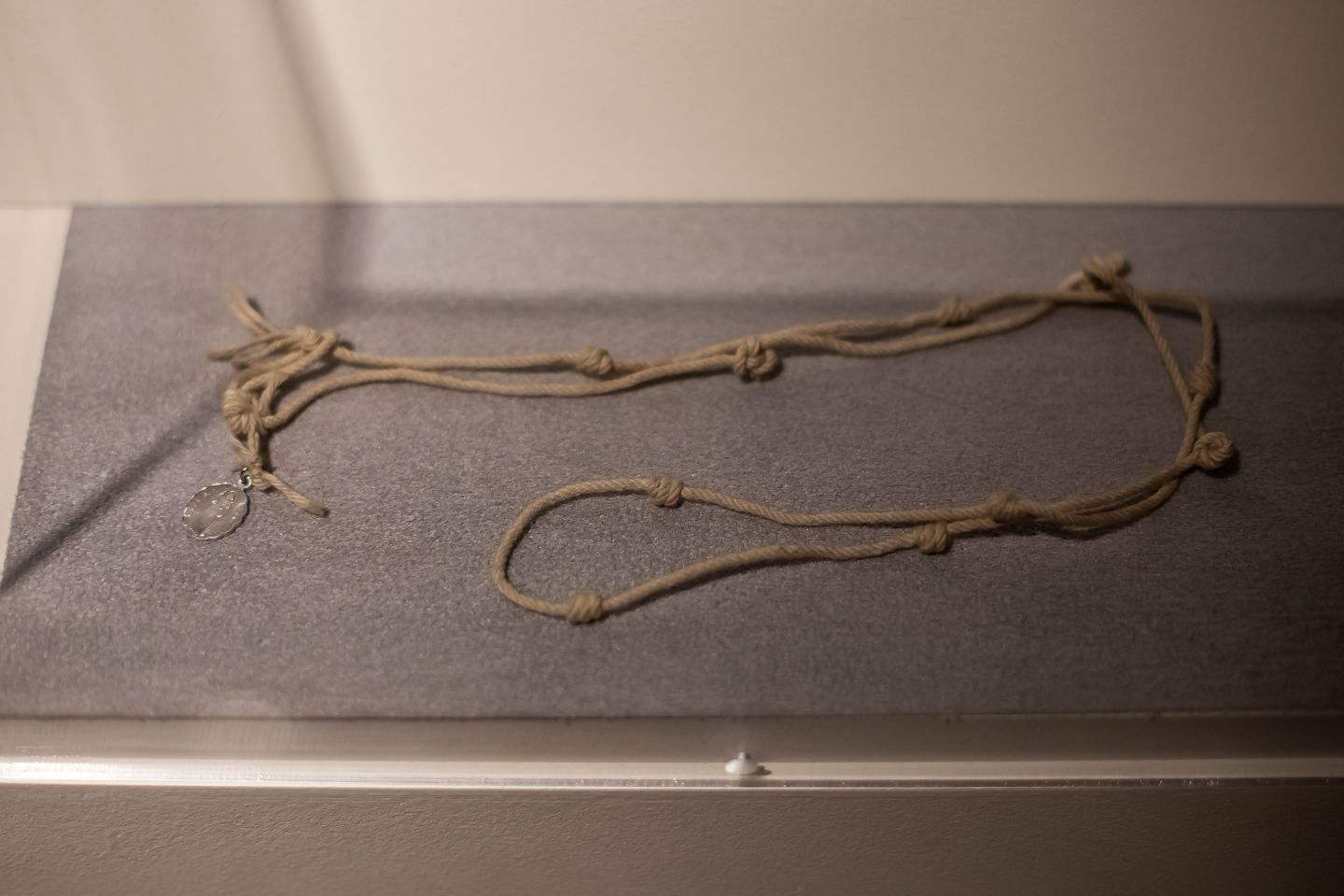

Forced From Land and Culture: Removal

Following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, thousands of Native Americans were removed from their homes in the Great Lakes and east coast regions to Indian Territory. On the morning of Sept. 4, 1838, a band of 859 Potawatomi, with their leaders shackled and restrained in the back of a wagon, set out on a forced march from their homeland in northern Indiana for a small reserve in present-day Kansas. More than 40 died along the way. Today, the trek is known as the Trail of Death.

West of the Mississippi

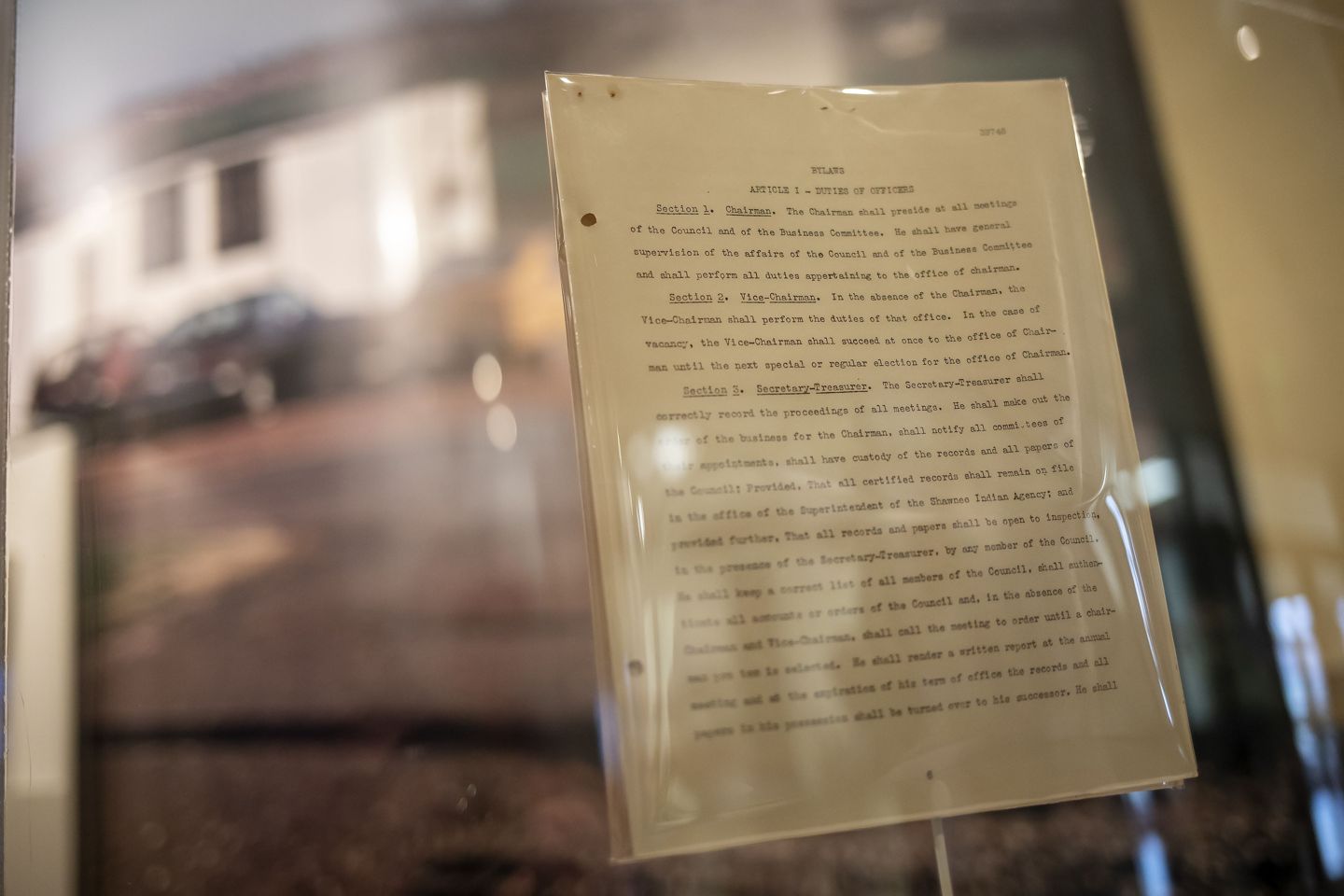

In 1846, the scattered Potawatomi settlements in the West were consolidated onto one reservation on the Kansas River. Some tribal members adapted to a sedentary lifestyle, but they did not assimilate to the degree desired by the federal government. To remedy that, on November 15, 1861, a few dozen tribal members signed a treaty that initiated the process for acquiring land allotments and U.S. citizenship. This group became known as the Citizen Potawatomi.

Indian Territory: A Place to Call Our Own

The provisions for the Citizen Potawatomi’s move to Indian Territory were stipulated in a treaty signed on February 27, 1867. A delegation of Citizen Potawatomi travelled to Indian Territory and selected a tract of land to be their new reservation.

In 1890, the Citizen Potawatomi unwillingly participated again in the allotment process implemented through the Dawes Act of 1887. In the Land Run of 1891, the remainder of the Potawatomi reservation in Oklahoma was opened up to non-Indian settlement.

Seventh Generation

During the 20th century, CPN established a sound government, and the foundation created continues to direct the Nation. As soon as Citizen Potawatomi settled in present-day Oklahoma, Tribal members exercised their sovereignty through letter-writing campaigns and building relationships with all levels of government, and that tenacity remains today. Federal legislation like the Indian Self-Determination Act of 1975 made real reform possible. CPN has seen phenomenal growth since 1985, including job creation, expansion of services, and a revitalization of culture.

Wédaséjek

The Veteran Memorial serves to honor and exhibit the sacrifices our Wédasé (warriors) have made by telling the story of what it meant to be a Potawatomi warrior. It is a living monument to our proud Citizen Potawatomi Nation veterans and active-duty members. Currently, the memorial commemorates more than a thousand veterans and warriors and is continually growing. Also, check out the Veterans Wall of Honor.

DIGITAL EXHIBITS

Dancing For My Tribe

“The whole idea of my project is to capture the essence of Potawatomi traditions and create a place in history for the Tribe. Preserving the faces, stories, and regalia of modern Potawatomi will contribute to a better understanding of their transformed place in the diverse life of America.”

View Exhibit >>

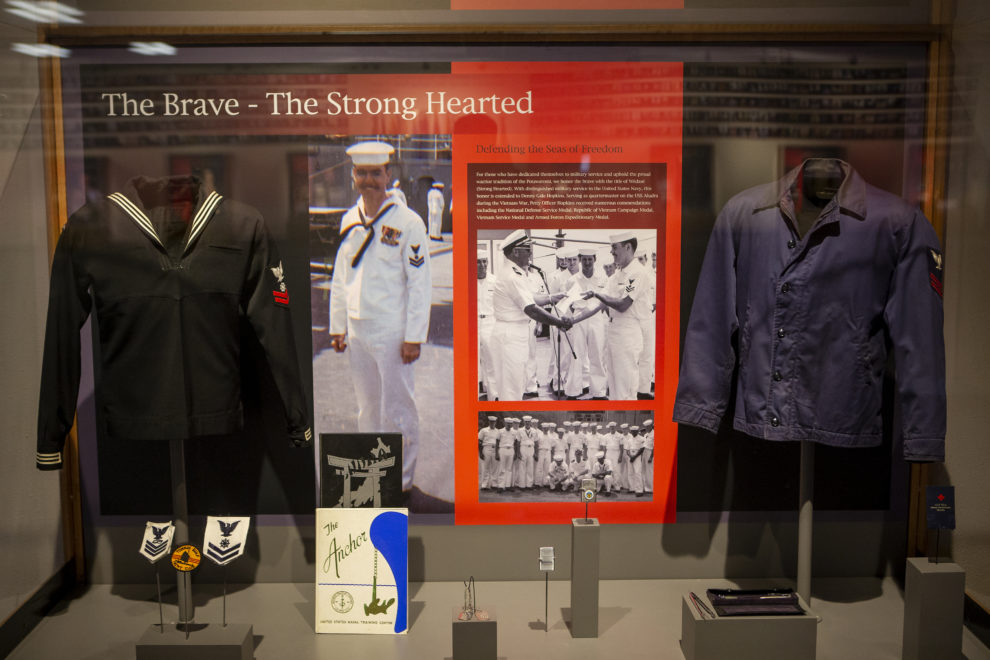

Defending the Seas of Freedom

For those who have dedicated themselves to military service and uphold the proud warrior tradition of the Potawatomi, we honor the brave with the title of Wédasé (Strong Hearted). With distinguished military service in the United States Navy, this honor is extended to Denny Gale Hopkins. Serving as quartermaster on the USS Aludra during the Vietnam War, Petty Officer Hopkins received numerous commendations including the National Defense Service Medal, Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal, Vietnam Service Medal and Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal.

View Exhibit >>

A True Hero

For those who have dedicated themselves to military service and uphold the proud warrior tradition of the Potawatomi, we honor the brave with the title of Wédasé (Strong Hearted). With an extensive and distinguished career in the United States Army, this honor is extended to Richard Vincent Johnson. For valor during the Ryukyu Campaign, Western Pacific Campaign and Battle of Okinawa during World War II, First Lieutenant Johnson received numerous commendations including the Bronze Star Medal [oak leaf cluster], Purple Heart and Commendation Medal.

View Exhibit >>