Makwéndek: We Remember

From Mnwate (Dgwaget 2023)

Consequence and Power: The Bodéwadmik Trail of Death

Dweget brings the return of the anniversary of the Bodéwadmik Trail of Death, we are reminded of the difficulties our families have faced as a result of forced removal. As Shishibéni (Citizen Potawatomi), we were party to many removals, such as those in 1832, 1835, 1836, 1837, the Trail of Death in 1838, the re-removal of escaped Bodéwadmik in 1851, 1872, and the removal of Shishibéni in 1891 by the Seventh Cavalry from Kansas to Oklahoma, to name a few.

Indian Removal and its legacy have defined our identities as Shishibéni and Mshkodéni (Prairie Band Potawatomi) Bodéwadmik. Between our two bands, we often remember the decades following Andrew Jackson’s signing of the Indian Removal Act into law in 1830 as some of the darkest in our history as Neshnabék. The devastation wrought upon the Bodéwadmik and Neshnabék permeates our lives as Neshnabék who live outside of Neshnabéwaki (homeland; land of the Neshnabé). Indeed, removal inaugurated our political and sociocultural liminality as people who bear the status of “removed.” That is to say: whatever we do as a people, politically, culturally or otherwise, may be on lands we call home but these are not our homelands. When we gather each year for our Festival and powwow; when we take buses north to the annual Bodéwadmi Gathering; when we gather as a community in any capacity, it serves as a reminder of our distance from Neshnabéwaki. We live in places further south and west than our ancestors ever knew. We are the legacy of Indian Removal.

Origins of Indian Removal

The story of removal can be traced to the very beginning of the United States. As historians like Jeffery Ostler and John Bowes have written, the founders of the American Republic aggressively pursued Indian removal as a remedy to the Indian resistance that plagued American expansion. In these early years, the Neshnabék and our allies broke American westward advance. Pontiac ground the engine of British imperial expansion to a halt; Little Turtle, with the aid of the Bodéwadmi, Odawa, Ojibwe and others, dealt the United States military the most significant defeat in its history; Tecumseh and his brother, the Shawnee Prophet Tenskwatawa, along with Bodéwadmi Wabeno, Main Poc and other Neshnabék at their side, led a resistance movement so fierce the British and the Americans believed a new Indian state would emerge from its aftermath as a permanent buffer to land-hungry Americans. As Philip Deloria has written, so intense was Neshnabék resistance to American expansion into Neshnabéwaki, that in 1794 George Washington tripled the size of the American army and redirected five-sixths of the entire United States federal budget for the sole and explicit purpose of neutralizing our resistance. All the energies (and most of the money) of the American government were committed to subduing the Neshnabék and our relatives in the last decade of the 18th century.

As the Americans slowly advanced into the heart of our homelands with each passing year, our strategies changed. We engaged, as we always had, in various diplomatic measures in an effort to circumvent violence. Yet treaty sessions increasingly entangled us in an unequal, often profligate system, that was as clear as it was honest. By the end of the 1820s and following the tragic end of Tecumseh’s war against the Americans, the memories of our resistance remained strong among those most designing Americans. They feared us. They feared our mnedo — our power. From the torch-bearing settler who set our cornfields ablaze as the first snows of bbon (winter) fell to the soon-to-be-president of the United States, Andrew Jackson, whose pen likewise set fire to the lives of the Neshnabék. They knew all too well our abilities and remembered our mnedo. The only way to deal with us was to remove us. Sword, pen, and torch were united in the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

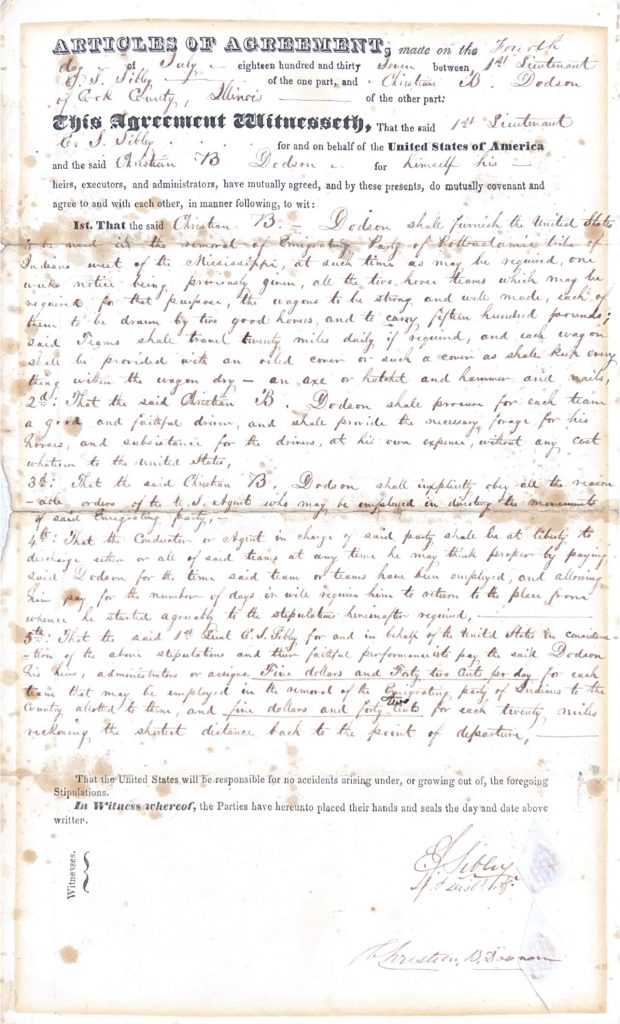

Beginning in Chicago in 1835, Bodéwadmik were compelled to remove by energetic and corrupt federal Indian agents. Indian removal became a lucrative enterprise, and an entire industry sprouted around the practice of removing communities like ours from our homelands. The process of removal was activated by treaties, a likewise profitable enterprise for traders, creditors and merchants seeking a cut of whatever payouts were promised by the federal government.

Signatory communities theoretically consented with full knowledge of the treaty and its stipulations to remove to the West, typically with the promise of government aid. The reality proved far different. Often, removal agents found ways to produce signatures on treaties by locating a few willing leaders alleging to speak for their communities, or by exerting overt pressure through outright threats. Moreover, treaties that stipulated Indian removal seldom made the expectations of removal clear. This kind of ambiguity and deceitfulness was not incidental to the practice of Indian removal; it was central. The full power of federal authority was wielded by these Indian agents to achieve the complete removal of all Native communities from Neshnabéwaki and paved the way for the systematic settlement of our homelands by Euro-Americans.

Treaties and The Trail of Death

The signing of the Treaty of Chicago by the Neshnabék and Bodéwadmik required that the Bodéwadmik and Odawek in the Chicagoland area remove by 1835. In September of 1835, the first Bodéwadmi removal took place from what is now America’s third largest city, initiating the long and tumultuous decades of Bodéwadmi removal, re-removal and migration.

However, several bands of Bodéwadmik resisted the Americans’ pressure to remove. Mnomen’s band in northern Indiana and southern Michigan was one such band. Mnomen, along with other Bodéwadmi wgëmek (“oh-gih-muk”: leaders), Peepinohwaw, Notawkah and Muckkahtahmoway managed to secure reservation lands in the treaty of 1832. As with many treaties, tensions escalated as settlers flooded into freshly-ceded lands. But they demanded more, and the land that the Bodéwadmik were unwilling to relinquish seemed especially appealing to these new arrivals.

Pursuing his mandate to rid the Great Lakes of Indians, Abel Pepper, an Indian agent in Indiana, aggressively pushed Bodéwadmik to cede their reservation lands established in 1832. Faced with staunch Bodéwadmik resistance, however, an increasingly frustrated Pepper met with little success. But Pepper found other means to extinguish Bodéwadmi land claims. Between 1832 and 1836, a series of illegitimate treaties were signed by tribal members without authorization from the bands that they purported to represent. Mnomen and 17 other delegates from his band abstained from the treaty negotiations in protest. The United States accepted the signatures of other tribal members claiming to speak on behalf of Mnomen’s band anyway, an act which band leaders established as a betrayal punishable by death in 1837.

Two years later, the deadline set by the 1836 treaty for Mnomen and the other bands to remove to Kansas had passed, and Pepper finally found his opportunity to remove the obstinate Bodéwadmik. On Aug. 30, 1838, General John Tipton and a contingent of Indiana volunteer militia surprised the Bodéwadmi at Twin Lakes, detained tribal leaders and hastily forced 859 Bodéwadmik to begin their march to Kansas at gunpoint. As the removal conductor William Polke recounts as their party departed the removal camp on Sept. 4, “provisions and forage rather scarce and not of the best quality.” With sickness quickly overcoming many of the Bodéwadmik, and with little food and water, the first child — a three-year-old — died on Sept. 8, just four days after the removal began. This was the first of many deaths along what we now remember as the “Trail of Death.”

The brutal reality of our ancestors was recounted at the time as a “necessity,” and as General John Tipton wrote of the Bodéwadmi Trail of Death, “It may be the opinion of those not well informed upon the subject, that the expedition was uncalled for, but I feel confident that nothing but the presence of an armed force, for the protection of the citizens of the State, and to punish the insolence of the Indians, could have prevented bloodshed” stating further that “[t]he arrival of an armed force sufficient to put down hostile movements against our citizens effected in three days, what counselling [sic] and fair words had failed to do in as many months.”

It remains difficult to understand just how necessary it was to take the lives of our children. We arrived in the West on Nov. 4, 1838, just as the first snows of bbon began.

Consequence and Power

In our lives as Bodéwadmi, we continually confront the lasting effects of our removal from Neshnabéwaki. And yet the very reason for our removal — our power — has been vigilantly protected by us. It was Pontiac, Little Turtle, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, with the aid of countless Neshnabék like Main Poc and Mnomen, who reminded the Americans that we were not, as the Europeans and Americans believed at the time, a dying race of people destined for extinction. Instead, we provided a generational buttress to Euro-American expansion, dealing significant defeats to the American military in open combat. They feared our knowledge, our connections to kin and land, and sought our eradication. And when they failed to achieve our total annihilation, their settler dreams were tormented by the memories of our victories. Removal was the colossal and final attempt by the United States to dispossess us, not just of the power of our physical presence in Neshnabéwaki, but the mnedo we hold as a people — as Neshnabék, as Bodéwadmi.

But if removal constitutes the source of our pain, it is likewise a reminder of our power. That we have survived these many years in Kansas and Oklahoma is a testament to the failure of the United States to extinguish our mnedo. We are annually reminded of our removals as we retrace them with our travels to Festival and our powwow or reconvene as a Bodéwadmi Nation at the annual Gathering, or in any moment when we come together. Our mnedo has remained with us as we remember these stories of removal. One day we will return to Neshnabéwaki, and we will carry with us the stories of all those who have become our kin in the western lands in which we now live. Until then, we will continue to remember what we have lost and remind ourselves of what we have kept.

Iw.